Once I was ready to risk my clearances and career for actions that had some (not necessarily great) chance of being helpful, new approaches occurred to me. I embarked on several of these simultaneously.

As one of these approaches, in October 1969 I began photocopying, with the initial help of my former RAND colleague Anthony Russo, the Top Secret 7,000-page McNamara study. In November I began giving the study to the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator William Fulbright. Despite the invasion of Cambodia in 1970, Senator Fulbright still held back from bringing out the documents in hearings, for fear of Executive reprisal.

After still another invasion (of Laos in 1971), I gave most of the study to the New York Times. When the Times was enjoined from publishing it further after three installments—the first such prior restraint in American history and a clear challenge to the First Amendment—I gave copies to the Washington Post and eventually, when the Post and two other papers were also enjoined, to nineteen papers in all. For all these papers to publish these “secrets” successively—in the face of four federal injunctions and daily charges by the Attorney General and the President that they were endangering national security—amounted to a unique wave of civil disobedience by major American institutions.

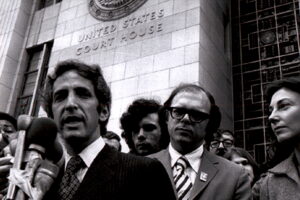

Just before the Supreme Court voided the injunctions as conflicting with the First Amendment, I was indicted on twelve federal felony counts, posing a possible sentence of 115 years in prison. My friend Anthony Russo, who had found a copying machine for me and helped with the initial copying, was charged on three counts. These criminal charges against a leak to the American public were just as unprecedented as the earlier injunctions. However, after almost two years under indictment and over four months in open court, all charges against us were dismissed “with prejudice”—meaning we could not be tried again—just before closing argument, on grounds of governmental criminal misconduct against me. That was another first in American jurisprudence.

What had happened was that when President Nixon learned, shortly after my first indictment, that I had also copied the Top Secret NSSM-1 from his own National Security Council and given it to Republican Senator Charles Mathias, Nixon reasonably, although mistakenly, feared that I had other documents from his own Administration, including nuclear threats and plans for escalation which had yet to be carried out. He secretly directed criminal actions to prevent me from disclosing such embarrassing secrets, including the burglary of my former psychoanalyst’s office in search of information with which to blackmail me into silence, as well as a later effort to have me “incapacitated totally” at a demonstration at the Capitol.

When these crimes became known, they led—besides the termination of our trial—to the criminal convictions of several White House aides. The same offenses, originating in the Oval Office, also figured importantly in the impeachment proceedings against President Nixon that led to his resignation in 1974.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1973, in the political atmosphere accompanying these revelations of White House crimes and cover-up, Congress finally cut off funding for further combat operations in Vietnam. The removal of Congressional support was crucial in the 1975 ending of the war.

—Daniel Ellsberg