Ever since 1969, I have pursued what amounted to two parallel careers, seeking as a researcher to improve understanding—my own and others’—of the very phenomena I and others were, at the same time, trying by our activism to change or avert: the dynamics and dangers of the nuclear era and of unlawful interventions, and abuses of the government secrecy system. Neither effort, it has seemed to me—of investigation or resistance—could safely be put aside to await the completion of the other.

Ever since 1969, I have pursued what amounted to two parallel careers, seeking as a researcher to improve understanding—my own and others’—of the very phenomena I and others were, at the same time, trying by our activism to change or avert: the dynamics and dangers of the nuclear era and of unlawful interventions, and abuses of the government secrecy system. Neither effort, it has seemed to me—of investigation or resistance—could safely be put aside to await the completion of the other.

As Thoreau said, “Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence.” I believe that the urgency of the need to reduce the dangers of nuclear war calls for every form of nonviolent political and grassroots activity—from letter-writing to Congress and editors to lobbying, political campaigning, lectures, teach-ins and demonstrations—in all of which I have participated.

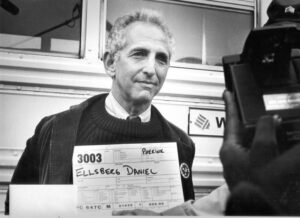

Likewise, I have sought to encourage and have participated in mass actions of nonviolent civil disobedience, which had had such a powerful effect on my own decision to release the Pentagon Papers. I have been arrested in non-violent civil disobedience actions close to ninety times, with over fifty focused on nuclear weapons: e.g. at the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Production facility, the Nevada Test Site, Livermore Nuclear Weapons Design Facility, and the vicinity of ground zero at the Nevada Test Site and at Vandenberg Missile Test Site. Other arrests have been in protest of U.S. interventions, including the lead-up to the Iraq War.

In retrospect, I see how much of a piece my professional life has been with respect to my several ongoing concerns as they extend into the present and future. This really began sixty-five years ago, with my academic work on decision-making under uncertainty. Even my years in the Marine Corps played their part, re-directing my intellectual interest in decision theory toward questions of national security. That led me to the RAND Corporation and the Defense Department, where I became aware of the dangers of our nuclear posture in concrete, terrifying detail, as is known to very few other civilians—including even high-level officials and dedicated anti-nuclear activists. Then my focus at RAND shifted to Vietnam.

In retrospect, I see how much of a piece my professional life has been with respect to my several ongoing concerns as they extend into the present and future. This really began sixty-five years ago, with my academic work on decision-making under uncertainty. Even my years in the Marine Corps played their part, re-directing my intellectual interest in decision theory toward questions of national security. That led me to the RAND Corporation and the Defense Department, where I became aware of the dangers of our nuclear posture in concrete, terrifying detail, as is known to very few other civilians—including even high-level officials and dedicated anti-nuclear activists. Then my focus at RAND shifted to Vietnam.

If I had remained in universities, I would probably have come to oppose the war, as so many others did, and I would have been even more likely than I was as a “defense intellectual” to meet Gandhian draft resisters. But I would not have brought to that encounter the burden of knowledge and sense of responsibility from my experience in the Pentagon, Vietnam, and the White House. I might not—indeed I could not—have responded to their example precisely as I did. As it was, their moral courage was contagious.

There has never been a greater need for civil courage in our citizenry and officials. Will it, can it be evoked in time? To have a basis for hope, we must speak and act as if it can. That is what my life and work are about.

—Daniel Ellsberg