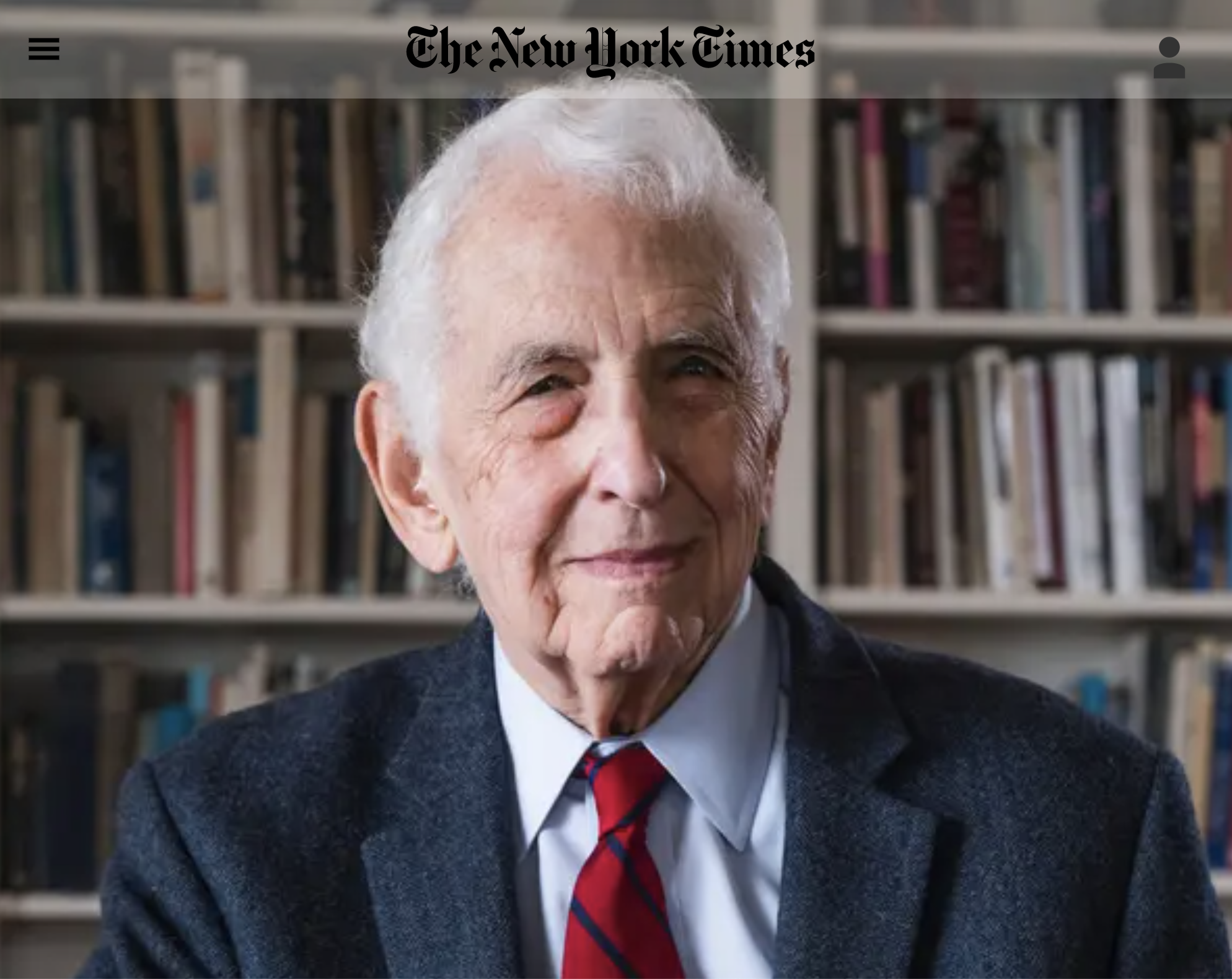

The New York Times recently published a Q&A interview and a podcast with Daniel Ellsberg:

The Man Who Leaked the Pentagon Papers Is Scared, by Alex Kingsbury – a Q & A with Daniel Ellsberg, New York Times, 3/24/23

Nuclear Secrets, a Compost Heap and the Lost Documents Daniel Ellsberg Never Leaked, New York Times podcast with Lulu Garcia-Navarro, 4/20/23

Excerpts follow from the just-released podcast.

Intro: At the end of his life, the man behind the Pentagon Papers has a warning for us all.

A few years ago, Ellsberg revealed a secret: the Pentagon Papers were only some of the documents he’d copied, and not even the ones he considered most important. There was another set of documents about American nuclear war planning that he had wanted to be his legacy. But a sequence of events involving his brother, a compost heap, the FBI, and a tropical storm kept Ellsberg from ever bringing those other papers to light.

Now Ellsberg is reflecting on his life. And against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine and rising tensions over Taiwan, he worries that we’re closer than ever to nuclear disaster and that the American public won’t start paying attention until it’s too late. Today, Daniel Ellsberg’s final warning.

Lulu Garcia-Navarro: So in those early days at RAND, beyond reading reports about the Russians, what was your actual job?

Daniel Ellsberg: Actually, I was working on a branch of economics called decision theory. My work was: how do people reasonably make decisions under conditions of great uncertainty or ambiguity? An enemy attack — this meant a Soviet attack at that time — would inevitably be ambiguous.

Our warning systems have misread flocks of geese and atmospheric disturbances for incoming attacks, sending false alarms. So how would the president decide what to do when he wasn’t sure if there might be an attack? He didn’t want his planes to be caught on the ground. But on the other hand, if he went first, it could be on a false alarm. So this was the most consequential decision under uncertainty that any human had ever faced. That’s what I was working on.

Garcia-Navarro: Clearly it didn’t take long after you started working at RAND for you to start to think that the safeguards in place to prevent nuclear calamity were not as robust as you might have hoped.

Ellsberg: No. That was my specialty, investigating that, and that was the conclusion I came to: this is a very dangerous system.

Garcia-Navarro: Did you ever actually see a nuclear bomb? Did you ever get close to one?

Ellsberg: The only time I recall seeing an actual nuclear weapon was in Kadena (Air Force Base) in Okinawa. There was a weapon on a trolley, the kind of thing that carries heavy things to be loaded on the plane. It was, I would have said, six or seven feet long.

I put my hand on it, and uncannily, it felt warm. It was a cold day, but the weapon was warm because there was radioactivity coming from it. It felt like animal heat. It felt as though it were alive. That was an eerie feeling.

Garcia-Navarro: I’m thinking of you as a young man discovering how faulty the systems are that keep us safe from nuclear war. Do you think things are any better now, considering what a dangerous situation we’re in with Russia and other places?

Ellsberg: We’re in a more dangerous situation than any time in my lifetime. You could say the Cuban Missile Crisis, which I was involved in, in fact had a comparable risk of all-out nuclear war; that’s true. Nothing since then.

…I’ve long said that to my last breath I will be doing what I can to postpone and avert the risk of nuclear war. And I will. I will do what I can to the last — till my last breath.