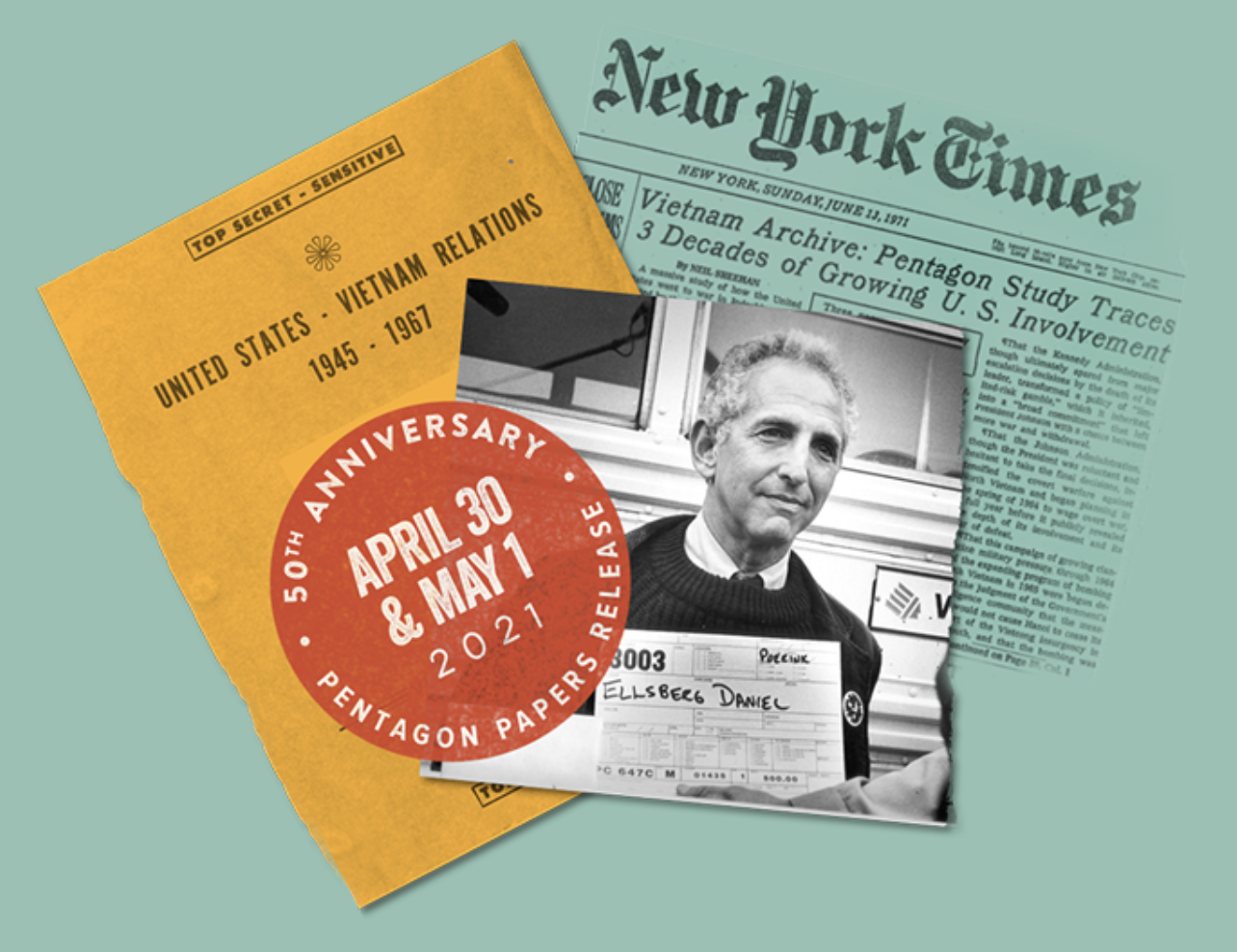

From Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers by Daniel Ellsberg, Chapter 25: Congress

In late December 1970 I had what turned out to be my next-to-last talk with Senator Fulbright, in his office, about what to do with the Pentagon Papers. He now had nearly everything I had, including NSSM-r and my notes on the Ponturo study of Tonkin Gulf. Norvil Jones had made it clear that there would be no public hearings on the war of the sort he’d envisioned back in May, during the Cambodian invasion. The public concern just wasn’t there anymore, nor was there support for such hearings on the Foreign Relations Committee itself. The war had scarcely been an issue in the November congressional elections. Fulbright himself didn’t disagree with my own urgent concern, after the failed Son Tay raid to rescue American prisoners of war, and the renewed bombing of North Vietnam, that the war would soon be getting larger, but he didn’t see much possibility of mobilizing opposition in Congress until that happened.

As for the Pentagon Papers, Fulbright seemed sympathetic to my desire to find some way, apart from immediate hearings, to bring them to bear on the continuing war. He mentioned a number of ways in which it would still be possible to get the papers out with relatively little damage to me, though that wasn’t my major concern. He raised the possibility of issuing a subpoena to Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird for the papers. He didn’t have to limit himself, he said, to requesting them from Laird, as he had done several times so far. He could demand them.

At this point Norvil revealed what I take it had been his real worry from the beginning. He thought that the committee, even if it got the papers from Laird by request or subpoena, couldn’t put them out to the public on its own, without administration approval. Even more, the chairman couldn’t do it on his own because he and the committee were supposed to safeguard for the Senate as a whole classified material, which they got all the time and for which they had storage facilities. If Fulbright leaked the papers or went ahead and distributed or published them, he could be charged with having jeopardized the ability to get classified material from the executive, not only for the committee or himself but for the entire Senate. Jones also mentioned that the committee members, and in particular its staff members, were often accused of leaking. It was easy for me to guess that Jones himself didn’t want to be accused of this. He had often shown great concern that I not reveal to anyone that I had given the papers to Fulbright.

Fulbright told me that he had asked Laird several times now for the study, but it seemed unlikely that he was going to get it. It was becoming clear to me that Jones was not going to encourage Fulbright to stick his neck out by releasing or using what I’d given him. Fulbright himself said to me, “Isn’t it after all only history?” I said, well, yes, but it seemed to me quite important history. It was also a history that wasn’t over yet. He said, “But does it really matter? Is there much in there that we don’t know?” He asked if I would give him an example of a revelation that would make a big splash.

Continue Reading